Bloomberg

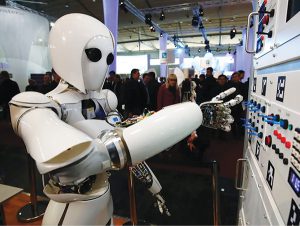

First they came for factory jobs. Then they showed up in service industries. Now, machines are making inroads into the kind of white-collar office work once thought to be the exclusive preserve of humans.

The latest wave of automation is building on advances in artificial intelligence and machine-learning that allow computers to perform tasks like speech recognition, and make some of the decisions that used to be reserved for employees. Unlike sophisticated machinery on assembly lines, or kiosks where consumers pay for groceries or order burgers, these are robots you can’t see.

The pandemic has ramped up demand for them. With wages rising fast, workers in short supply and near-record job vacancies, US businesses are racing to automate as much as they can.

Data is hard to come by. But on earnings calls this summer, executives at all kinds of firms — from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to clothing retailer Abercrombie & Fitch Co. — were touting their investments in AI and other kinds of automation.

It’s not just corporate giants, capable of spending millions of dollars to develop their own technologies, that are getting in on the act. One feature of the new automation wave is that companies like Kizen have popped up to make it affordable even for smaller firms.

Based in Austin, Texas, Kizen markets an automated assistant called Zoe, which can perform tasks for sales teams like carrying out initial research and qualifying leads. Launched a year ago, it’s already sold more than 400,000 licenses.

There are plenty of other ambitious companies cashing in on the trend, and posting steep increases in revenue — like UiPath Inc., a favorite of star investment manager Cathie Wood, as well as Appian Corp. and EngageSmart Inc.

Alongside the growth of AI and what economists call “robotic process automation†— essentially, when software performs certain tasks previously done by humans— old-school automation is still going strong too.

The number of robots sold in North America hit a new record in the first quarter of 2022, according to the Association for Advancing Automation. The World Economic Forum predicts that by 2025, machines will be working as many hours as humans.

The upbeat view says it’s tasks that get automated, not entire jobs — and if the mundane ones can be handled by computers or robots, that should free up employees for more challenging and satisfying work.

The downside risk: occupations from sales reps to administrative support, could begin to disappear — without leaving obvious alternatives for the people who earned a living from them. That adds another employment threat for white-collar workers who may already be vulnerable right now to an economic downturn, largely because so many got hired in the boom of the past couple of years.

The likeliest outcome is a bit of both, with “many winners and many losers,†according to Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David Autor, a leading scholar in the field.

In particular, Autor warned in a recent paper, “computerisation increases the productivity of highly educated workers by displacing the tasks of the middle-skill workers who in many cases previously provided these information-gathering, organisational, and calculation tasks.â€

Those employees have been under pressure for some time. Back in 2014, research by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas found that mid-skill, routine jobs — in sales or administrative support, for example — had been declining since the 1990s, especially during recessions.

Many adopters of the new automation technologies say they haven’t cut jobs as a result.

Some of the biggest firms at the forefront of automation also say they’ve been able to do it without cutting jobs.

Engineering giant Siemens AG says it’s automated all kinds of production and back-office tasks at its innovative plant in Amberg, Germany, where it makes industrial computers, while keeping staffing steady at around 1,350 employees over several decades.

The firm has developed a technology known as “digital twinning,†which builds virtual versions of everything from specific products to administrative processes. Managers can then run simulations and stress-tests to see how things can be made better.

Whatever the outcome, it’s unlikely to allay the deep unease that the idea of automation triggers among workers who feel their jobs are vulnerable. With the rise of AI, that group increasingly includes white-collar

employees.

Higher productivity — essentially a measure of how much output is generated from each hour of work — is the holy grail of economics, and one of the key goals of automation.

So far, at least, all the pandemic innovation in the US hasn’t led to better outcomes.

Productivity slumped in the first half of 2022. That means businesses — which were hiring at a rapid clip in the period, and paying higher wages — ended up spending more money on each unit they produced, when automation should help them to spend less.

To be sure, productivity numbers are volatile and subject to lots of revisions. It can take a long time for the fruits of innovation to show up in the data. And if the US is poised for a slowdown or even a recession, as many expect, that will likely add even more incentives for companies to invest in AI and robotics. Research suggests that when economies shrink, leaving firms with less revenue to pay their workers, automation tends to speed up.

Whatever the outcome, it’s unlikely to allay the deep unease that the idea of automation triggers among workers who feel their jobs are vulnerable. With the rise of AI, that group increasingly includes white-collar employees.

The Gulf Time Newspaper One of the finest business newspapers in the UAE brought to you by our professional writers and editors.

The Gulf Time Newspaper One of the finest business newspapers in the UAE brought to you by our professional writers and editors.